LOS ANGELES — LA is often criticized as a city with a short historical memory, one that paves over the past in search of the new. Two recently unveiled public artworks at the Los Angeles County Hall of Records offer alternative perspectives on the sprawling metropolis, making visible overlooked, forgotten, or marginalized communities and places.

Earlier this month, artists Teresa Baker (Mandan/Hidatsa) and Felix Quintana led a discussion with a small group assembled outside the Department of Regional Planning (DRP) on the 13th floor of the Hall of Records in downtown LA. Their artworks were commissioned by the Los Angeles County Department of Arts and Culture and overseen by Los Angeles Nomadic Division (LAND). The total budget for the project was $150,000, including artist honoraria and production costs.

Baker’s 17-foot-long astroturf assemblage, “Wenot (Life Giver)” (2024), hangs within a recessed alcove in the building’s lobby, its arched form framing a long modernist green couch. Its colorful geometric shapes recall an aerial map; however, Baker was quick to note that the work suggests more than represents actual geography.

“When I started, I felt an obligation to do more of a concrete mapping of LA, and then I kind of had to scrap that because I just don’t work that way,” she told Hyperallergic.

A few signifiers of specific places emerge among the abstract forms, though, such as a horizontal blue line referencing the LA River. The work’s title, “Wenot,” means “life giver” in the Kizh language of the Gabrieleño Band of Mission Indians, who refer to the river by this name.

According to the terms of the commission, the pieces will remain on view for 25 years, meaning that conservation was a prime concern for the artists. Baker collaborated with ethnobotanist Matt Teutimez (Gabrieleño Band of Mission Indians – Kizh Nation) to select native plants to incorporate, such as acorns, mule fat, elderberry, and willow, that would honor the area’s Indigenous history while remaining resilient well into the future.

“I guess it’s a romantic idea, really thinking about the future of LA by remembering the past and not just glazing over it with more concrete,” Baker said. “It’s such a rich land here, and it offers so much more than we’re really using.”

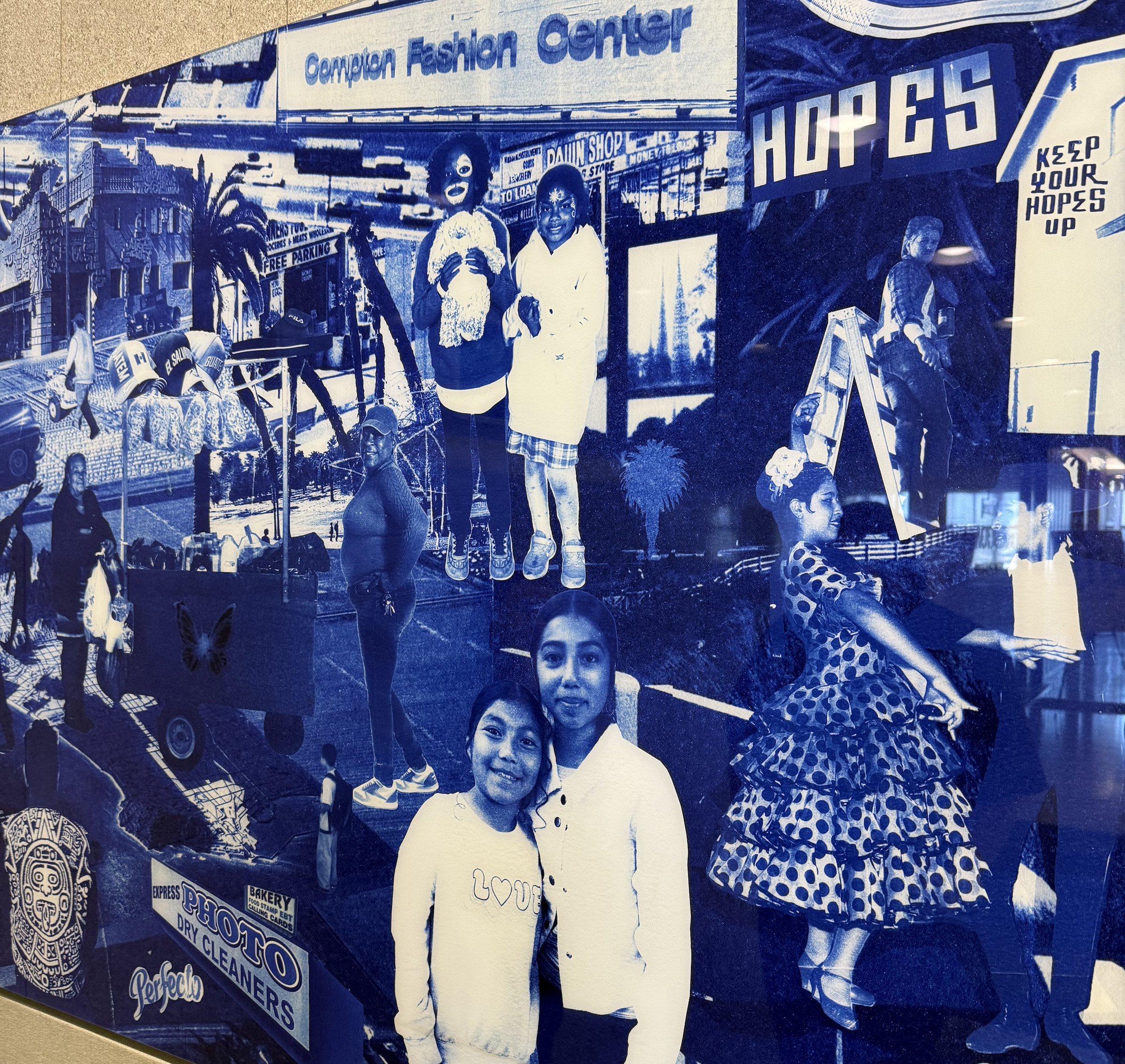

When visitors exit the elevator on the 13th floor, they encounter Quintana’s layered photographic collage “La sal de la tierra (The Salt of the Earth)” (2024). The Salvadoran-American artist, who grew up in Lynwood in Southeast LA County, eschewed a statistically accurate demographic map in favor of a personal vision of the city.

“Maybe I can’t show everybody, every experience. I wanted to be more honest to my own,” Quintana said.

The work includes his own photographs of people and places that hold personal meaning, with images drawn from the vast archives of the DRP: an aerial shot of Lakewood, a model post-war planned community in LA County; the now-defunct Compton Fashion Center, a swap meet and hip-hop mecca where NWA sold their first cassette tapes, immortalized in videos by Tupac and Kendrick Lamar; a photo of his grandmother crocheting; the iconic Watts Towers; an artwork by prolific LA graffiti artist Hopes; a nearly century-old photo of people playing soccer in MacArthur Park, as they still do today.

“The piece is kind of like a flattening of the past, present, and, hopefully, a little bit about the future of LA, the way I see it,” Quintana noted. He also incorporated community photos taken at three pop-up portrait studios he staged with LAND in Boyle Heights, Watts, and at the DRP offices.

As did Baker, Quintana had to contend with conservation issues, given that he regularly uses a cyanotype photographic process, which produces monochromatic blue images that can fade when exposed to light. He scanned his original cyanotypes, digitally collaging them to arrive at the final archival pigment print.

The Hall of Records was designed in 1962 by famed architect Richard Neutra, who called it “the world’s largest filing cabinet.” Although most of its archives have since been moved offsite, it still represents the recorded history of LA, what civic leaders decided was important enough to remember, while the Department of Regional Planning shapes the city’s future.

Baker recalled that there was initially a disconnect between the literal, pragmatic way DRP employees conceived of the city, its spaces, and people and the non-representational geometries, lines, and colors in her work. But “they were open to that at the end,” Baker explained.

“I was surprised because it is very abstract, so it’s exciting that they want it to live here,” she said.