Cartoonist Barbara Shermund was a young art school graduate when she made her first contribution to the New Yorker: a bold illustration of a woman riding the night bus on the cover of the June 13, 1925 edition. The magazine, which published its first issue 100 years ago this month, carved a niche in the crowded 1920s landscape of American periodicals with its distinct art direction and tongue-in-cheek coverage of local cultural life. As one of the New Yorker‘s first women cartoonists, Shermund created single-panel cartoons drawn with a seemingly off-the-cuff fluidity of line and expression that came to define its now-iconic sense of humor.

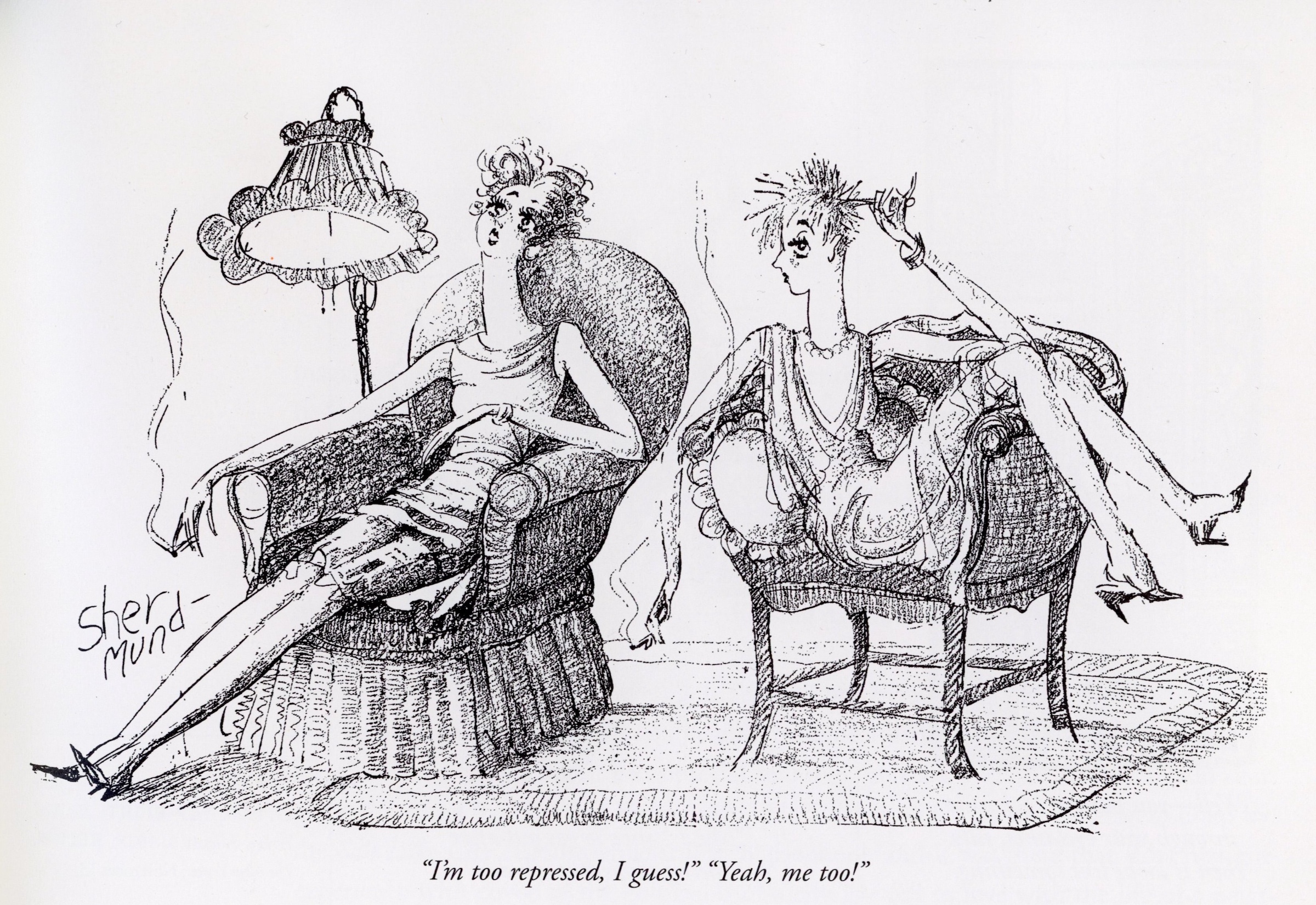

Born in San Francisco in 1899, Shermund moved to New York in 1924 to make her way as an artist. Her early cartoons centered on the character of the flapper — fashionably dressed, outspoken, and sexually liberated — whose comic interactions with other character types painted a picture of life in 1920s New York. Rendered in lines as crisp as the finest etching, and a sense of flapper style and posture drawn from life, Shermund’s young women gossiped in delis and on the subway; they smoked cigarettes and danced late into the night with married men; they woke up, horribly hungover.

And while Shermund may have lampooned her flappers, her sharp social commentary took relationships between young women seriously, recognizing the true, even subversive solidarity between them. There’s a knowing wink under all that eyeshadow — each gossipy comment is a whispered secret.

By foregrounding intimate moments between women, Shermund not only mainstreamed a more feminist point of view in the New Yorker but created space for queer interpretations of her cartoons at a time when public queerness was not widely accepted. While we are not certain how Shermund herself identified, as Caitlin McGurk writes in her excellent 2024 biography Tell Me a Story Where the Bad Girl Wins, we do know that her social circle of unconventional artists included queer and polyamorous people, who, like the flappers, made their way into her cartoons.

As a closer look at her cartoons reveals, Shermund may have treated these moments of queerness with queer audiences in mind. As with flappers, she’s not afraid to incorporate LGBTQ+ people in her cartoons, but a knowing kindness seems to underpin her acidic humor. If there was a queer character in a cartoon, the punchline tended to make more fun of the reader’s assumptions than of the character themselves.

For example, a 1926 black-and-white cartoon depicts three people in a park: two men, whom a knowing 1920s reader would quickly clock as gay, and an androgynous person, who is smoking a cigarette seductively. In comparison to the men, the androgynous person’s gender presentation is deliberately ambiguous, making the punchline — that the gay men decide they’re a woman, obviously, due to their “sex appeal” — all the more humorous.

There was certainly a limit to queer representation in the early pages of the New Yorker — in 1928, for example, a cartoon about a butch lesbian buying a bathing suit was reworked to be more palatable to straight audiences, and McGurk writes in her biography of Shermund that another about a trans man went unpublished.

As the social landscape of the United States grew more conservative from the 1930s to the 1950s, so too did Shermund’s cartoons. But her work from the early days of the magazine, particularly as the government threatens the health and freedom of trans people today, offers us a glimpse of a sexually liberated and feminist American society, a queer utopia of sorts that’s worth holding onto.