This article is part of a series focusing on underrepresented craft histories, researched and written by the 2024 Craft Archive Fellows, and organized in collaboration with the Center for Craft.

I chase ghosts! That is, I investigate the forgotten spirits and legacies of enslaved and free potters in Texas during and after the Civil War in the United States of America. This journey began with a 1991 conversation with my graduate advisor John Brough Miller, professor of ceramics at Texas Woman’s University in Denton, Texas, during which he shared the legend of John McKamie Wilson and enslaved potters in Seguin, Texas. Nearly a quarter century later, in 2014, an internet search led me to the website of the Wilson Pottery Foundation, created by the descendants of Hiram, James, and Wallace Wilson, the founders of H. Wilson and Co. Pottery. Three years later, in 2017, I attended the annual Wilson Pottery Show at the Sebastopol House in Seguin and was surprised by the amount of Wilson antique pottery on display and the number of collectors of it. I left the show with a heightened interest in the Wilson Potters.

In 2018, Tarrant County College District, where I was an assistant professor of Ceramics, awarded me faculty leave to research the H. Wilson & Co. Pottery, which is located in Capote, Texas, approximately 48 miles east of San Antonio and 12 miles east of Seguin. A search on Ancestry.com led me to a database of United States craftspeople ranging from 1600 to 1995, which lists Hiram Wilson as the founder of H. Wilson and Co. Pottery. Hiram was formerly an enslaved potter at the Guadalupe Pottery owned by John McKamie Wilson from Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. Scholars believe H. Wilson and Co. Pottery was the first business owned by an African American in Texas.

A deeper dive led to the other Wilson Potteries (designated as sites by the Texas Historical Commission, which identifies them by number) in the Capote area, including the aforementioned Guadalupe Pottery (41GU6), which was the first Wilson pottery site operated by John McKamie Wilson and his enslaved potters. H. Wilson & Co. (41GU5) was the second site, started by formerly enslaved potters from the Guadalupe site. The third Wilson pottery site (41GU4) was the Durham-Chandler Pottery, owned by Marion “MJ” Durham, a White man, and John Chandler, a formerly enslaved potter trained in the acclaimed Edgefield District of South Carolina. (These sites are often referred to as “First Site,” “Second Site,” and “Third Site” by collectors to help differentiate the pottery produced at each. Second Site pieces, for instance, are more valuable than First Site pieces.) After Hiram died in 1884, H. Wilson & Co. was believed to have merged with Durham-Chandler to become Durham-Chandler-Wilson. According to the United States Craftsperson Files database, Durham-Chandler-Wilson was founded in 1870, which may indicate that Hiram worked at the third site with James, Wallace, and other itinerant potters.

I propose that the relationship between these three sites might stretch back further than folklore holds. What if Marion “MJ” Durham and John McKamie Wilson’s families knew each other in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina? What if Durham was one of the primary investors in the Guadalupe Pottery with John McKamie Wilson? A partnership with Durham would support Wilson’s decision to build a pottery company in Capote. As a member of the Durham potting dynasty in South Carolina, the former certainly possessed the knowledge and pottery production skills to ensure a sound investment.

During my faculty development leave, I visited local historical societies, which were warm and informative. Some locations were rich in artifacts, whereas others had a wealth of documentation supporting the local community. On top of attending the 2018 pottery show at the Wilson Pottery Museum in the Sebastopol House in Seguin, I interviewed Wilson’s descendants, collectors, and others who shared various stories that led them to the show. One gentleman shared his salt-glazed one-gallon H. Wilson & Co. stamped pot he purchased at a thrift store in Austin, Texas. One notable takeaway from this interview session was how often collectors referenced San Antonio-based Texas pottery scholar and pediatrician Dr. Georgeanna Greer. She helped rediscover the Wilson potteries after the sites had been dormant for over 50 years; I discovered the depth of her research when I visited historical societies in East Texas. I was overwhelmed and excited to find letters written by her to local archivists requesting or sharing information on local pottery sites.

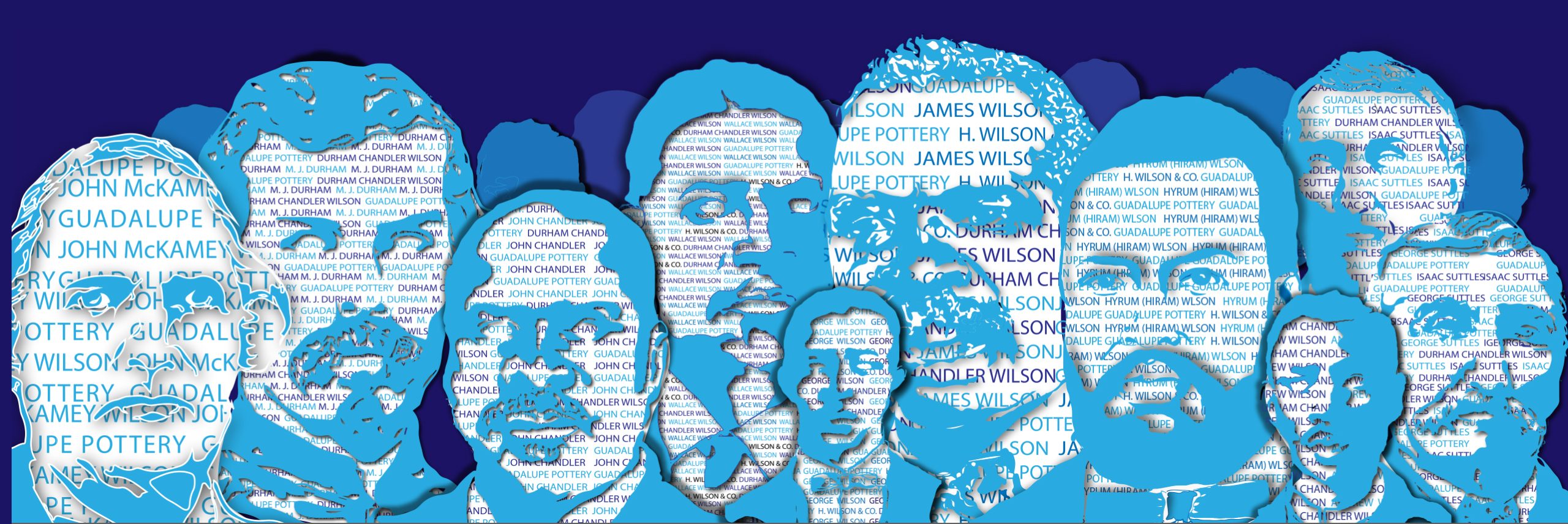

In 2020, I curated a solo exhibition in the Carillon Gallery at Tarrant County College South Campus in Fort Worth, Texas, which suggested a narrative and timeline to these potters by tracing the development of certain techniques. The centerpiece of the show, however, was not the ceramic pieces inspired by the Wilson potters and created for the exhibition, but rather the research identifying those who worked at one or more pottery sites seen via posters, including James and Wallace (and possibly Hiram) Wilson. Pots attributed to the first site, Guadalupe Pottery, suggests that Isaac and George Suttles, potters from Ohio, may have introduced the salt glazing technique found on pieces attributed to the first site’s pottery, as the practice originates from those trained in the North. The Suttles brothers later opened a pottery near Lavernia, Texas.

The discovery of this extensive pottery community in Capote redirected my focus toward East Texas, known as the entry point of Texas westward expansion. A visit to the William J. Hill Texas Artisans and Artists Archive was crucial to helping me collect information on East Texas potters. A visit to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s Bayou Bend Collections and Garden was also helpful in allowing me to examine Wilson Pottery from all three sites. Through the former, I located a “Checklist of Texas Potters ca 1840-1940,” compiled by Bob Helberg. This list provided names of formerly enslaved potters in the East Texas region, such as Milligan Frazier, A. Prothro, Elix Brown, and Joseph Cogburn. This in turn opened up another world of research possibilities. What if the pottery of the shops praised for their magnificent work such as Guadalupe Pottery were actually produced by trained enslaved laborers instead of the shop’s namesake? In other words, did the early Texas potters continue the industrial enslavement system that made Edgefield District in South Carolina famous?

This research is just a start. As I journey from central Texas back to Edgefield, South Carolina, searching for pottery families who migrated west before 1860 with their enslaved labor, bits and pieces of sherds are coming together to recreate the life stories of these potters. A beautiful mosaic is beginning to emerge.