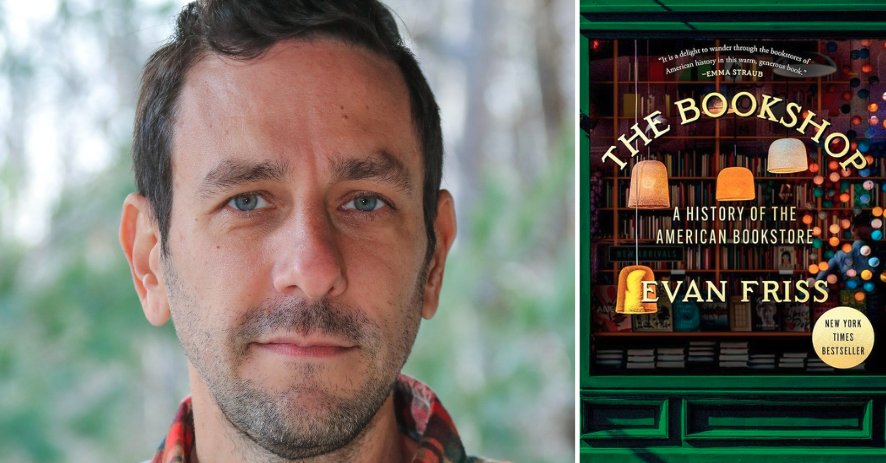

In The Bookshop: A History of the American Bookstore, history professor Evan Friss explores how bookstores have shaped reading, publishing, politics, and community, beginning in the 18th century. I talked with Friss about the value of indie bookstores, the bygone dominance of Barnes & Noble, and bookselling as activism.

Lenny Picker: How did this book originate?

Evan Friss: In 2003, I moved to New York to start graduate school studies in American history, with my then-girlfriend, now wife Amanda [now the owner of Harrisonburg, Virginia’s independent bookstore, Parentheses Books], who was looking for a job. She meandered around Manhattan, trying to think about something that would be joyful for her as a place of work, and she stumbled into Three Lives & Company in the West Village. They had very few employees at the time, and it worked out. She got a job there, but neither of us really knew how legendary that shop was, or how important bookstores were to large swaths of the local population. We were both serious readers, but we found that we would often talk more about the people at the bookstore—the regular customers, editors, authors, people who came in with their dog—than books. It became apparent to me just how important Three Lives was as a kind of community destination, a fixture of the neighborhood. I grew up in suburban Baltimore. There was a Barnes & Noble near us, but I wasn’t really used to an independent bookstore, and hadn’t had a lot of experience in one. So it was really through Amanda’s experience at Three Lives that I began to wonder, as a budding historian, about the history of the bookshop in America. The idea was seeded for potentially writing a book one day about how this institution emerged in America, how it evolved, and trying to understand its decline, and what it meant. Much to my surprise, no one had written such a history before, which worked out well for me.

LP: What did your research reveal that surprised you?

EF: I was born in 1980, and I know the kind of suburban mall, and the suburban department store, which had no book sections. Although malls were popular, none of these spaces had any kind of glamor by the time that I encountered them as a teenager. So the notion that they could have been not just luxurious spaces, but have distinguished book sections, was something that I didn’t know anything about until I started my research. What was particularly surprising was that Marshall Field’s book department wasn’t just a book section within a bookstore, but was almost a stand-alone bookstore. The woman who ran it, Marcella Burns Hahner, was a leading figure in American bookselling. She spoke at trade conferences. Other bookstores tried to emulate her model. She didn’t receive a lot of flack for being a sellout and having a corporate kind of bookstore, the way that B&N, and Borders, in the 90s, were criticized. Hers was a behemoth, corporate sort of giant bookstore that also was lauded for its service, for its curation, and for its ability to match books with customers.

LP: One of the things that surprised me was the extent to which Marcella Hahner had an impact on what was published. In the superstore era, was there a similar connection between what the stores published, and what publishers actually put out?

EF: Yes. One of the fascinating things is just how influential booksellers have been in determining what gets published, but also what gets sold and seen. That goes back to a Boston publishing house, Ticknor and Fields, who were deciding who to publish, but they were also retailers, looking at what people want to buy. They were looking at the kinds of books people were picking up as objects. What attracted them? What did the bindings look like? And this influenced their choices, and their shop helped make people like Nathaniel Hawthorne national names. Fast forwarding to the 20th century, I’ve heard from many other people that B&N, as an institution, used to have veto power on the cover design of basically any major book that was published by the publishers, such as a new Stephen King book. The publisher would come up with a couple of designs, and it would have to satisfy the author, the author’s agent, and B&N. And if B&N didn’t like the cover, it wasn’t going to be the cover. Publishers would also pay for premium space for their books, and the degree to which B&N pushed a book, and the degree to which a publisher paid to have B&N push a book, could really make the difference between a successful launch and a failure. Today, the closest thing is Amazon; it’s not that Amazon can veto a cover, but marketers and designers are thinking about what their book covers look like on a flat screen and designing around that as much, or more so, than thinking about what it’s going to look like in a bookstore.

LP: Your discussions of bookstores as sometimes serving as community centers reminded me of Eric Klinenberg’s 2018 book, Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life. In what ways do libraries and bookstores interact?

EF: When libraries first became popular, booksellers panicked that this would be the end of their business, because there were going to be these institutions that would loan books for free. For the most part, the relationship was relatively icy. But in much more recent times, especially in the post-superstore and Amazon era, one of the interesting shifts is that bookstores and libraries have become allies, and often cooperate with one another in ways that really wasn’t very common a century ago. Both institutions have had similar struggles and feel, to some degree, like they’ve had to reinvent themselves. They also see themselves as places to bring people together, and a lot of times, libraries and bookstores will pool their resources to bring in big name authors that maybe neither could afford to to pay for, and the bookshop will be there selling books, and the library will help promote it. They’ve also often rallied together in recent times against efforts to ban books and combat censorship.

LP: What else surprised you in your research?

EF: How many people, who got into the book business for non-financial reasons, weren’t people who read hundreds of books a year. A significant number, especially the activist booksellers, were hardly readers at all. The New York Public Library has the papers of Craig Rodwell, who started the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop. In digging through his personal files and letters, I came across his report cards—he failed English, and never appeared to be a serious reader. And yet, he opened one of the most remarkable bookstores in American history, and it came out of an impulse to educate and activate people.

LP: Can you expand a bit upon the impact of the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop?

EF: When Craig Rodwell started the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, he knew nothing about bookstores. He knew nothing really about literature, and he basically had tried to push another civil rights organization to have a sidewalk table to hand out literature to people. And he, like others, thought that the gay rights campaign would be improved by informing people about homosexuality, by introducing people to literature in which not all of the same kind of prejudicial tropes were evident. His whole mantra was “gay is good,” and had the idea of creating a space to make people not feel ashamed about being gay, but proud of it, and part of that was going to introduce them to books, fiction, and nonfiction, to help normalize what it meant to be a gay person in America. This was a a very, very radical thing to do, to open, a bookstore which had glass windows, facing the street, even in the West Village, which was a more progressive place than many other places. He got death threats, and there was violence, and people threw rocks through the window. Rodwell was a really remarkable and courageous person, and he saw the bookstore as the chief way to organize a movement. He was at the center of the response to the Stonewall riots and was one of the founding fathers of the City’s gay pride parade. To him, activism and bookselling were one and the same. He created this space, where people from all over the country wrote letters to him for advice. People were desperate to work there. The number of people who cite popping into Oscar Wilde as a kind of seminal moment in their own life is just astounding.