LONDON — What does poetry look like? It usually makes shapes on a page. Often these shapes are regulated — so many beats to a line. It often divides itself up into relatively small and boxy visual units called stanzas or strophes. It has been like that for millennia.

From the 17th century on, much poetry written in England was defined by a 10-beat line called iambic pentameter. In the 19th and 20th centuries, dramatic changes to the way poetry was made and thought about took place. The old rules began to break down under the hectic pressures of modernity. Other rules began to shoulder their way into the drawing room. Baudelaire wrote great prose poetry in prose — poeme en prose. The American poet William Carlos Williams talked of the line as breath; the length of a line could relate to a single out-breath.

A key player in all of this change to the way poetry was looked at, written, and thought about was a didactic shouter of a man called Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, founder of an Italian movement called Futurism. This all began in 1909. Futurism is much about art, but experimental poetry played a key role in its development, too, as we discover when we visit the exhibition Breaking Lines at the Estorick Collection in north London, the only public museum in the city wholly devoted to 20th-century Italian art.

Marinetti’s fervent wish was to foster, create, and bellow about the headlong dynamism of his present moment, with its speed and its giddying mechanization. The past was a heap of smoldering ruins, best ignored altogether. The destructive force of the First World War could help to wipe the slate clean. A part of this revolution had to do with the re-fashioning of poetry, that ancient discipline. Marinetti grabbed poetry by the heels and shook it until its teeth rattled.

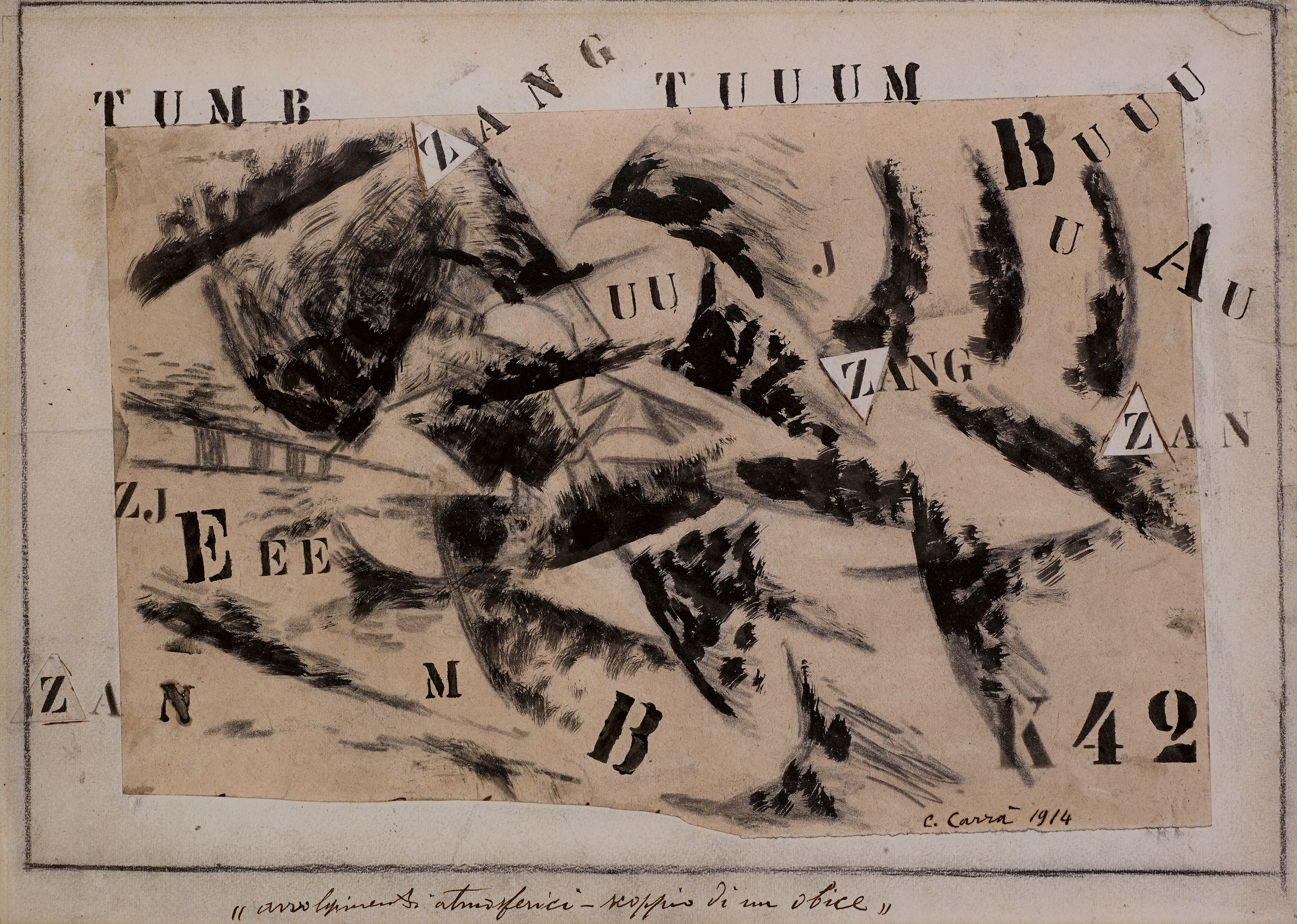

Marinetti’s wish was to free verse from its shackles of tradition. Syntax could go — as could any vestige of reasoned argument. Feeling, intuiting the swing, sway, and pressures of life, with all its tumult, its blare, its bounce, and its heave, were what really counted. And so it is no surprise that the walls of this exhibition should be showing off such words as these: ZANG TUMB TUMB scrABrrRrraaNNG — which are snatched from an experimental poem written by Marinetti himself.

To present these words sequentially, as if part of a sentence, after the politesse of a colon, is not to do them full justice. The fact is that when we look at them on the wall of Gallery 1, they are not walking in a straight line at all. They hang around each other. They swoop and they dive and they swing, often curvaceously. Not a single font articulates them, but several. They are not book-bound, but aerial, words in flight. Their sounds are a key to their impact — the entire exercise is a riot of onomatopoeia. In fact, these are not so much words as sounds. It is, in short, something of a crazed word-cum-soundscape. Its mood is feverish.

Poetry was on the mood, leaping off the wall, something of a street marauder. And it has kept on running and running, for dear life.

Breaking Lines continues the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art (39a Canonbury Square, London, England) through May 11. The exhibition was curated by the museum.